-

TrendsPolarizationSocial MediaDiversity, Equity & Inclusion

-

SectorOthersIT and Communications

-

CountriesGlobal

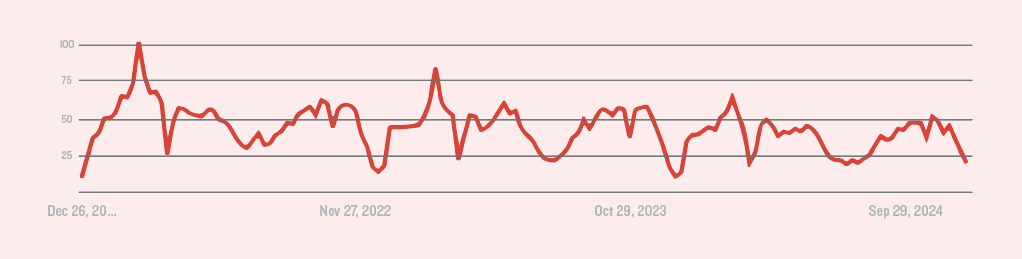

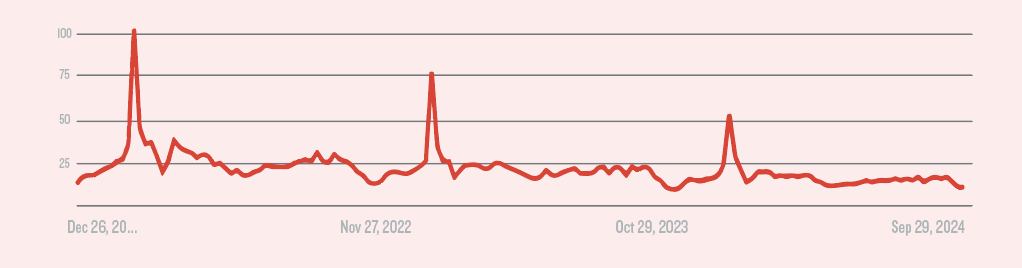

Equality is losing ground. Over the past three years, interest in the topic has declined, reflected in a 60% drop in web searches—50% in the case of feminism. Additionally, multiple studies confirm a growing ideological divide between genders, particularly among younger generations. According to the Financial Times, less than half of Gen Z men view the cause as legitimate, compared to 72% of women who support it.

Internet search trends on equality-related topics worldwide.

Equality is not just fading as a social concern—it’s also facing a reputational crisis. In online conversations, one in two critical messages about equality denounces it for its supposed ideological bias and radicalization. In other words, half of those who oppose equality do so because they perceive it as an extreme movement, exaggerated and tied to partisan interests. Meanwhile, the few skeptical voices who express doubts about equality (2%) don’t engage in the debate. From their moderate stance, they don’t identify with the “radicalism” that antifeminist narratives have assigned to the movement.

This led us to a key question: Are feminists really that radical? And how extreme are those who accuse them of being so?

It’s undeniable that the conversation around equality is polarized. Simplifying greatly for ease of understanding, we could say that a conversation is considered polarized when more than 80% of social interactions align strictly with one side or the other—meaning there are only two opposing viewpoints. At LLYC, we use various metrics to quantify these scenarios, assessing volume, hostility, divergence, and overall sentiment. While non-polarized discussions tend to be richer and more diverse (featuring multiple perspectives, reflections, and opinions), polarization isn’t always toxic. For example, the debate over whether a Spanish omelet should include onions is highly polarized, but it’s not necessarily hostile (usually).

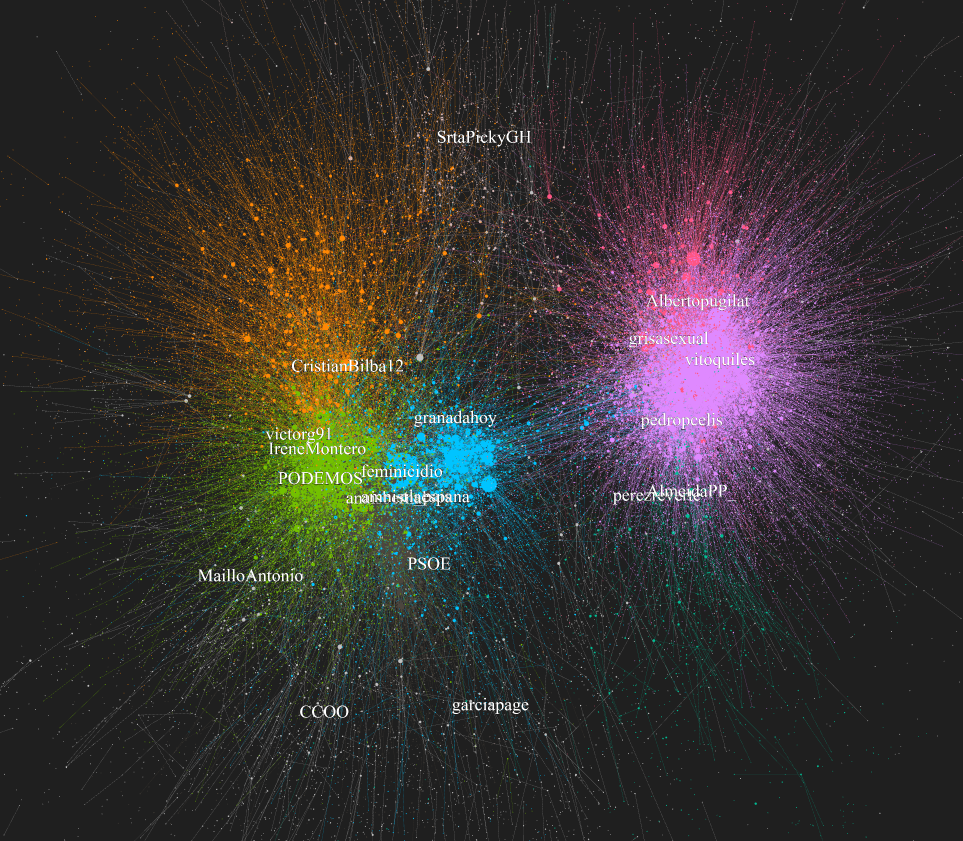

Given this, we needed a methodology that could map out the structure of each side in order to test our hypothesis. That meant diving deeper into the communities that exist in opposition to each other.

LLYC’s sociograms classify communities based on interaction metrics. This means that users in a given group may not necessarily discuss the same topics but engage with each other as “tribes” or networks. This segmentation is made possible through clustering algorithms (in this case, Louvain. Once we divided these communities into two major camps, we zoomed in on each stance and conducted further analysis through our Innovation department.

Spain’s feminist (left) vs antifeminist (right) sociogram.

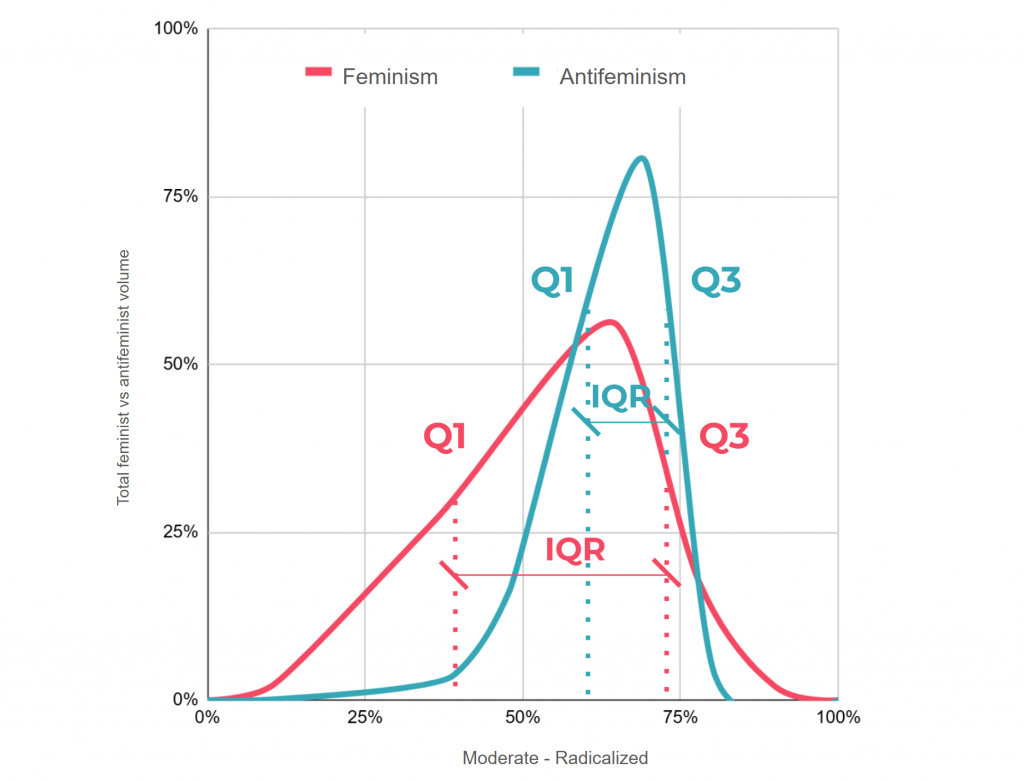

Each side is composed of multiple sub-communities. To break these down further, we applied density metrics based on the interquartile range (IQR) and relevance thresholds to filter out noise.

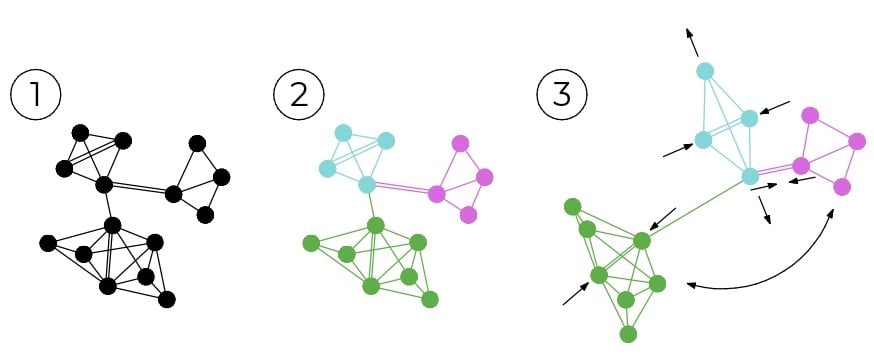

Our methodology

1.- We collect social media conversations using a predefined query, isolating discussions about equality within a specific time frame and country. We then represent this conversation as a graph, where nodes illustrate user profiles and the lines connecting them indicate interactions (reposts). Research shows that, in almost all cases, reposting—unlike replying or liking—signals ideological alignment.

2.- To categorize communities, we use the Louvain algorithm, which optimizes groupings based on modularity. Modularity measures the density of connections within communities compared to the density of connections between communities. Since models like this infer solutions through algorithms without being trained on labeled data, they fall under the category of unsupervised learning.

3.-Virtually all analyzed conversations about equality are polarized, which means that the sociogram is aligned along a single axis: one end represents the pro-equality stance, while the other represents the opposing ideological position. This characteristic allows us to work with a projection of values along an axis. The process of reducing from two dimensions to one (from a sociogram to an axis) is called dimensionality reduction.

Figure summarizing the first three steps. Recurring interactions are represented with double lines.

4.- Profiles closer to the center of the axis are more moderate, while those near the extremes are more radical. The same principle applies to communities. After projecting these profiles onto the axis (typically grouped into bins or intervals), we obtain a distribution—a density diagram—where greater height represents a higher concentration of profiles within that interval.

Here the interquartile range of the feminist faction is up to three times larger than that of the antifeminist faction, demonstrating greater diversity among its communities.

Results and conclusions

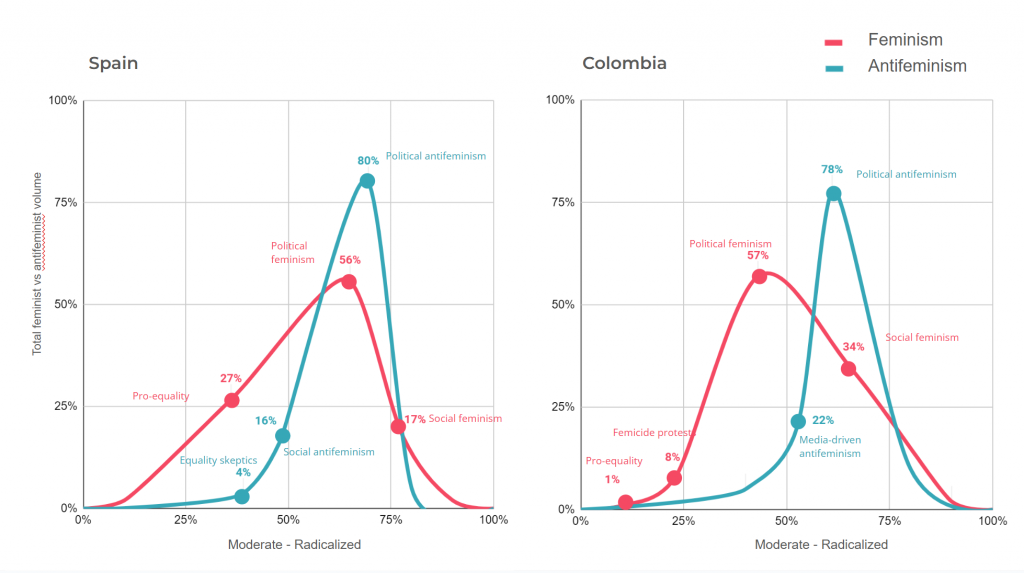

The findings are revealing. Globally, pro-equality factions are 17% more dispersed than antifeminist groups—and in countries like Spain, Colombia, and Ecuador, they are twice as dispersed. They are generally composed of communities with more diverse viewpoints. Sociograms reflect this fragmentation through multiple distinct communities, while density diagrams show it in broader distribution curves (feminists) versus more concentrated, less moderate curves (antifeminists).

Density of feminist and antifeminist sectors based on their degree of radicalization in Spain and Colombia.

In other words, the pro-equality space fosters a variety of opinions on issues such as gender violence, workplace equity, and diversity, encouraging richer debate—even allowing for internal disagreements. In contrast, the antifeminist faction operates as a monolithic group with a single, clear objective: discrediting a caricature of feminism that they themselves have created:

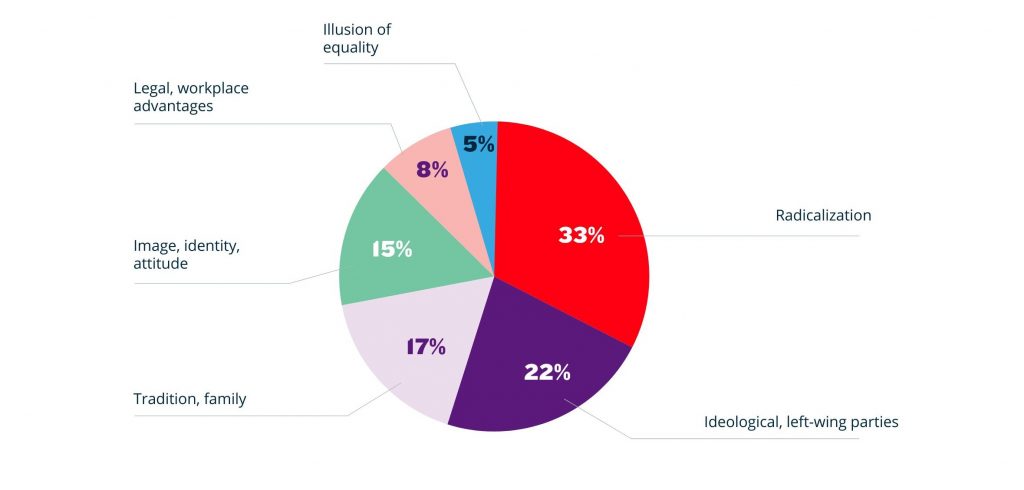

Most common attributes used by the antifeminist faction to stigmatize pro-equality stances.

From a technical standpoint, the concentration of communities within each faction serves as a key indicator of radicalization: the more concentrated a group, the more dogmatic and uncritical its stance. But there are other supporting factors:

- 1 in 3 antifeminist messages is brief and emotionally charged, whereas pro-equality messages tend to be 10% longer, offering more reasoning and reflection. Unfortunately, social media algorithms often reward emotionality and “easy” diffusion, giving these shorter messages greater engagement.

- 4 in 5 antifeminist messages (80%) are politicized, while the pro-equality sector typically shows 50% politicization.

- An equality skeptic is 1.6 times more likely to become radicalized than a moderate pro-equality supporter. This is largely due to the greater diversity of communities within the feminist stance and the lower presence of political discourse in the most widely disseminated feminist communities.

- Hate speech is significantly more prevalent in antifeminist spaces. While the most common derogatory terms used by feminists are “misogynist” or “backward,” the antifeminist faction frequently resorts to slurs such as “whore” or “frigid.”

Despite our research clearly showing that the association of equality with radicalism and partisanship is misguided—especially when compared to its ideological opposition—the antifeminist stance is gaining traction. This is precisely because it is more emotional, more immediate, more politicized, and more dogmatic. Social media algorithms “reward” this kind of behavior, as engagement metrics confirm. The challenge for the equality movement is to counteract this perception and communicate the benefits of a more equal society.

LLYC’s equality reports aim to contribute to this effort. Most recently, No Filter tackled this complex challenge by analyzing digital conversations, identifying key trends, and proposing measures that benefit society as a whole.

To explore these findings further, you can access the full report here and watch the video here:

Alejandro Buegueño

Global Innovation Senior Consultant